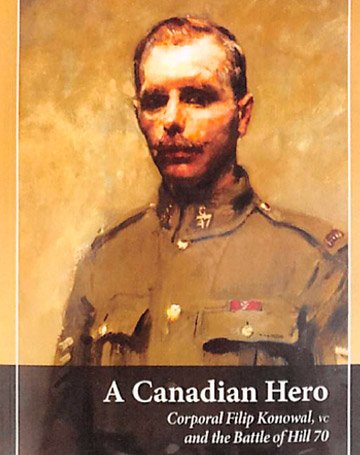

A Canadian Hero. Book sponsored by the Ucrainica Research Institute

← All projects

Filip Konowal, a Ukrainian Canadian volunteer serving as a corporal with the 47th Canadian Infantry Battalion of the Canadian Expeditionary Force, fought with exceptional valour in August 1917 during the battle for Hill 70, near Lens, France. For his courage, Konowal was awarded the Victoria Cross, the highest decoration of the British Empire, by King George V in London on 15 October 1917. His Majesty remarked: Your Exploit is one of the most daring and heroic in the history of my army. For this, accept my thanks.

After being hospitalized in England, Konowal was officially assigned for a time as an assistant to the military attache of the Russian Embassy in London. Later he was transferred to the 1st Canadian Reserve Battalion, served with the Canadian Forestry Corps and eventually with the Canadian Siberian Expeditionary Force. He returned to Vancouver on 20 June 1919, after soldiering for three years and 357 days in the ranks of the Canadian Army, one of as many as 10,000 Ukrainian Canadians who had so served. Ironically they did so at the same time as many of their compatriots were being unjustly interned and otherwise censured as "enemy aliens" during Canada's first national internment operations of 1914-1920.

As the M.P. for Edmonton East, Mr. H.A. Mackie wrote to Prime Minister Robert L. Borden on 16 October 1918: At the beginning of the war, hundreds or thousands of Ukrainians from Russia enlisted with the Canadian Expeditionary Forces as Russians, and no doubt the Canadian military statistical bureau would today show that most of these so-called Russians came from districts which are now in the territory comprising the Ukrainian State. Canadian recruiting officers soon discovered that those so-called Russians were nothing other than of the same stock as Ukrainians. Because they were not allowed to enlist as Austrians, they used fictitious names and gave false places of their birth to show that they came from Russia, some even calling themselves "Smith" and other English names. To estimate the number of Ukrainians who have enlisted in this way with the Canadian Expeditionary Forces would be very hard, as they were enlisting in various battalions from the Atlantic to the Pacific coast, but it is safe to say that, to the approximate half million soldiers in Canada, if the figures of the War Office were available, it could be shown that these people, per population, gave a larger percentage of men to the war than certain races in Canada have, after having enjoyed the privelages of British citizenship for a period of a century or more.

Honourably discharged, Konowal was subsequently troubled by medical and other problems, most thought to be a consequence of his war wounds. Nevertheless, by 1928, he had begun to rebuild his life. He enlisted in the Ottawa-based Governor General's Foot Guards. He re-married in 1934, taking for his second wife a widow, Juliette Leduc-Auger. (His first wife, Anna, and their daughter, Maria, were in Ukraine during the Stalinist terror and their whereabouts were unknown.) Thanks to the intervention of another Victoria Cross winner, and also a member of the Governor General's Foot Guards, Major Milton Fowler Gregg, Seargeant-at-Arms of the House of Commons (1934-44), Konowal found employment as a junior caretaker in the House of Commons, a humble job, but, in the years of the Great Depression, a welcome one. Spotted washing the floors of the Parliament building by Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King, Konowal was reassigned as the special custodian of Room No. 16, the Prime Minister's office, a post he held until his death. While others might bemoan Konowal's apparently low employment status, the man himself was much more sanguine. As Austin F. Cross reported in The Ottawa Citizen on 16 June 1956, when Konowal was asked about being a janitor he laughingly remarked, "I mopped up overseas with a rifle, and here I must mop up with a mop.” He also revealed something that was not recorded in the official account of how he won his Victoria Cross: I was so fed up standing in the trench with water to my waist that I said the hell with it and started after the German army. My captain tried to shoot me because he figured I was deserting.

Konowal was again acknowledged for his valour during the 1939 Royal Tour when His Majesty King George VI shook his hand during the dedication of the National War Memorial in Ottawa. He also kept in touch with his wartime comrades, even attempting to fight for Canada during the Second World War, an impossibility given his age.

___________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________