Articles

____

|

Danylo Czajkowsky’s book “I Want to Live” can now be purchased ($20). It’s a memoir about Ukrainian political prisoners incarcerated in the Nazi German concentration camp Auschwitz. Danylo Czajkowsky - intellectual and political activist- dedicated his whole life to a passionately held goal: the realization of a free, independent, sovereign and united Ukraine after centuries of foreign rule. In pursuit of this dream, he endured deprivation and persecution, incarceration in Nazi German prisons and concentration camps, and, later, assassination attempts by the Soviet Russian secret service. |

____________________________________________________________________________

Published in the bulletin Canadio-Byzantina, no. 36, University of Ottawa, January 2025, pp. 18-20.

RESEARCH ON ARCHAEOLOGICAL FINDS FROM BATURYN,

UKRAINE, IN 2024

In 1995-2021, Ukrainian and Canadian archaeologists and historians carried out annual excavations in the town of Baturyn in north eastern Ukraine, the capital of the early modern Cossack state or Hetmanate. Because of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, any field investigations in Baturyn were suspended in 2022-23. However, scholars at the Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies (CIUS) at the University of Alberta and the Hetman Capital National Historical and Cultural Preserve in Baturyn have continued their off-site research on the important artefacts, discovered during the extensive excavations in this town before the war.

The project of archaeological and historical study of Baturyn has been sponsored by CIUS and the Ucrainica Research Institute in Toronto (www.ualberta.ca/canadian-institute-of-ukrainian-studies/centres-and-programs/jacyk-centre/baturyn-project.html, www.ucrainica.ca/our-projects/74). Prof. Zenon Kohut, a former CIUS director and an eminent historian of the Cossack polity, initiated this Canada-Ukraine undertaking in 2001. Presently, he acts as its academic adviser and participates in the publication of the research results. The Ukrainian Studies Fund in New York also supports the Baturyn project.

In 2022-24, Baturyn and its environs were spared from Russian occupation, bombardments, and destructions. Past summer, archaeologists at the Hetman Capital National Historical and Cultural Preserve and some volunteers resumed the limited excavations in this town. Remnants of several ordinary burghers’ dwellings from the Byzantine era and early modern period were unearthed in Baturyn’s vicinities. These new archaeological findings will be examined and published in 2025.

In 2023-24, the researchers of Baturyn published the booklet and series of articles on the glazed ceramic and terracotta (unglazed) tiles featuring the angels or cherubs found before the war (fig. 1). They faced the heating stoves at the opulent baroque palace of the distinguished Cossack elected ruler, Hetman Ivan Mazepa (1687-1709), which was constructed in the Baturyn suburb of Honcharivka prior to 1700. His residence was burned by tsarist troops when they ravaged Baturyn in 1708 suppressing Mazepa’s insurrection for the independence of Ukraine from Muscovy. Debris of the Honcharivka palace was excavated in 1995-2020.

Our publications on these stove tiles are richly illustrated with photos of their original fragments and hypothetical reconstructions of several complete specimens, as well as the front elevation of the most costly glazed ceramic polychrome tiled stove from Mazepa’s ruined manor using photo collage and computer graphic techniques (figs. 2-6). The authors have closely examined the reliefs and enamel paintings of the stylized bodiless angels with only head and two outstretched wings on the Baturyn tiles. These are broadly compared with this motif represented on the early modern majolica dishes, repoussé works, Orthodox icons, engravings, book illustrations, and sculptural decorations of architecture in Kyiv, Western Ukraine, Poland, and Italy (e.g., figs. 7, 8).

Our research has shown that the stove tiles with angels excavated in Baturyn are valuable and informative pieces of Ukrainian artistic ceramics from the late 17th century. They were crafted by the skilled tile-masters, whom Mazepa summoned from Kyiv. In general, the motif of bodiless angels with only head and double wings was uncharacteristic of the Orthodox iconography of Byzantium and Kyivan Rus’. It appeared in the 15th-century sacral art of Renaissance Italy. From there, the angels or putti as a religious symbol, and later increasingly as merely ornamental element, were disseminated in both ecclesiastical and secular sculpture and painting all over Christendom during the 16th-18th centuries. At that time, this motif was also transferred to Ukraine primarily via Poland. It became favourite in the sculptural and pictorial embellishments of Orthodox and Catholic churches, monasteries, castles, palaces, crypts, tombs, as well as in the secular and icon paintings, book graphics, artistic metal and earthen wares of Western and Central Ukraine (e.g., figs. 7, 8).

In the 16th and early 17th centuries, invited Italian sculptors and painters introduced this motif to the arts of Galicia, Volhynia, and Kyiv, then under dominion of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. Since that time, the Kyivan tile-makers could model the reliefs and frescoes of putti in the late Renaissance style which adorned the interiors of the Assumption Cathedral at the Cave Monastery and St. Sophia Cathedral in Kyiv, as well as their depictions on Western and Ukrainian baroque engravings, book illustrations, Catholic icons, European secular paintings, toreutics, and other artistic imports.

Young Mazepa was brought up at the Polish royal court and studied and travelled in Germany, Holland, France, and Italy in 1650-60s. He was fascinated with European arts, literature, and culture and promoted them in Ukraine. Mazepa could decorate the tiled stoves at his residence in Baturyn with the motifs of angels of the Renaissance tradition as a tribute to the art fashion then prevalent in the West and Kyiv, and as indication of his European cultural orientation (figs. 2-6).

Thus, our research of the images on the stove tiles excavated in Baturyn provide an important insight into the culture, lifeways, and artistic interests of the hetman, Cossacks or burghers, and their reception of the stimulating artistic influences from Kyiv and the West. It shed new light on the hitherto little known culture of the Cossack Ukraine capital and its link to European Christian civilization.

Our 2023-24 booklet and two articles discussing the Baturyn stove tiles with angels in detail in Ukrainian and English with many illustrations are available online in PDF format (fig. 1):

www.academia.edu/118018338, www.academia.edu/124016543,

www.academia.edu/121259407/Angels_Adorning_Ivan_Mazepas_Palace_in_Baturyn. The researchers of Baturyn intend to continue the excavations there next summer, if the wartime conditions in Ukraine permit.

Volodymyr Mezentsev, Ph. D.

Executive Director

Canada-Ukraine Baturyn Project

CIUS Toronto Office

Email: v.mezentsev@utoronto.ca

FIGURES (8)

Fig. 1. Our booklet in Ukrainian titled in translation “Angels in the Decoration of Ivan Mazepa’s Palace in

Baturyn: A Study Based on Archaeological Findings” (Toronto: “Homin Ukrainy”, 2023).

Fig. 2. Half of the glazed ceramic polychrome tile with the angel’s image from the facing of the stove

at Mazepa’s palace in Honcharivka. All photos by V. Mezentsev, line drawings by S. Dmytriienko.

Fig. 3. Fragments of the glazed ceramic tile featuring an angel from the stove revetment of

the Honcharivka palace.

Fig. 4. Photo collage of the entire glazed ceramic polychromatic stove tile with the angel

by S. Dmytriienko.

Fig. 5. Complete stove tile bearing the angel in relief and covered by the multicoloured enamel.

Hypothetical computer graphic reconstruction by S. Dmytriienko.

Fig. 6. Front elevation of the upper part of the most ornate glazed ceramic polychrome tiled stove decorated

with the tiles depicting angels from Mazepa’s palace in Honcharivka, ca. 1700. Hypothetical reconstruction

and computer graphic by S. Dmytriienko.

Fig. 7. The 18th-century ceramic majolica multicoloured slab with the angel in bas-relief from the façade

adornments of the Assumption Cathedral at the Cave Monastery in Kyiv. Repository of the National Preserve “Sophia of Kyiv”.

Fig. 8. The 17th-century icon of the Holy Theotokos with the Baby Jesus and the high reliefs of four

angels. Hetman Capital National Preserve in Baturyn.

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________

Canadian Ethnic Politics and Canada's Policy Towards the USSR's 'Ukrainian Question',

Thomas Prymak, PhD, University of Toronto, Chair of Ukrainian Studies

1.

In 1916 Manitoba abolished Ruthenian (Ukrainian) bilingual schools - Preview #1

https://youtu.be/9Mi3drlnz5o

Mackenzie King rejected Polish request to control Ukrainians in Canada - Preview #2

https://youtu.be/PJPOHy-ZzdQ

During WW2 Ukrainian Canadians were forced to toe the line with the Grand Alliance - Preview #3

https://youtu.be/mWBxrX20tCc

Security Service of Ukraine wants to publicize the other side of the Soviet era - Preview #4

2.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cVE4AcV4D0s

0:33 Settlement of Ukrainian immigrants primarily in Western Canada map

1:23 Kingdom of Galicia and Lodomeria map

2:18 Dnieper Ukraine, 1850 map

3:00 Imperial Austrian-Hungarian passport of Andriy Prymak

17:10 Mykhailo Hrushevsky would often have lunch with Ivan Franko

22:16 Canadian Farmer newspaper, June 1941, Hitler, Marshal, Stalin, Molotov

26:48 Louis St. Laurent, William Michael Wall (Василь Волохатюк)

28:19 Oseredok - Ukrainian Culture and Educational Centre founded in Winnipeg, 1944. PM Louis St. Laurent took communion in a Ukrainian church which greatly impressed Ukrainians

31:56 John Diefenbaker

33:52 John Diefenbaker defended Ukrainians against Khrushev at the United Nations

35:05 Nikita Khrushev, Lavrentiy Beria

43:10 John Diefenbaker and Howard Greene at the UN, 1960

49:39 Wasyl Kushnir, Mykola Pidhirny

1:00:07 Expo '67 Montreal

1:05:10 Pierre Trudeau wins Liberal nomination

1:08:11 Pierre Trudeau visits Moscow, USSR, Spring 1971. Walter Deakon is his translator.

1:08:44 Pierre Trudeau and his wife Margaret visit Kyiv, Ukraine

1:13:46 Ukrainskyi Holos 1971, UCC President Wasyl Kushnir

1:20:34 Students protesting against Alexei Kosygin in Winnipeg, supporting Valentyn Moroz

1:23:00 Paul Yuzyk Fathers of Multiculturalism

1:31:55 Brian Mulroney visits Kyiv, Ukraine, November 1989

3.

How many human beings have been liberated by the USSR? - Preview

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=35WngbzGrN0

The Cold War was triggered in Ottawa by the Gouzenko Affair - Preview

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=p_R1mIhbp2g

Canadian Ethnic Politics and Canada's Policy Towards the USSR's 'Ukrainian Question', Thomas Prymak - Full remarks

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cVE4AcV4D0s

Video by UkeTube Ukrainian Video

This video was not sponsored. Please make a donation to support more Ukrainian content:

https://www.paypal.com/donate/?cmd=_s-xclick&hosted_button_id=SSTGBK265LXK4

______________________________________________________________________________________

ANGELS ADORNING IVAN MAZEPA’S PALACE IN BATURYN

Published in Ukrainian Echo, Vol. 38, No. 12, Toronto, June 18, 2024, pp. 1-3.

Zenon Kohut (Edmonton), Volodymyr Mezentsev (Toronto), Yurii Sytyi (Baturyn)

For 25 years until 2021, Ukrainian and Canadian archaeologists and historians carried out annual excavations in the town of Baturyn, Chernihiv Oblast (fig. 1). Unfortunately, Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022 suspended further field investigations. In the meantime, however, scholars at the Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies (CIUS) at the University of Alberta and the Hetman Capital National Historical and Cultural Preserve in Baturyn have continued their off-site research on the important artefacts, discovered during the extensive excavations in this town in 1995-2021.

The Canada-Ukraine Baturyn Archaeological Project is administered by The Peter Jacyk Centre for Ukrainian Historical Research at the CIUS Toronto Office (https://tinyurl.com/ypx3tdx2). Prof. Zenon Kohut, a former CIUS director and an eminent historian of the Cossack state, initiated this project in 2001 and he currently acts as its academic adviser and the co-author of our publications. Archaeologist Dr. Volodymyr Mezentsev, research associate at CIUS in Toronto, is the project’s executive director. Archaeologist Yurii Sytyi of the Hetman Capital National Preserve leads the Baturyn archaeological team.

So far, Baturyn has been spared from Russian occupation, bombardments, diversions, and destructions. Its five museums of antiquities, as well as the reconstructed citadel, hetman palaces, court hall, and churches of the 17th to 19th centuries, have been safely preserved and continue to receive many visitors (fig. 1).

In 1669, Baturyn was selected to be the capital of the Cossack realm, or Hetmanate. The town reached its zenith during the illustrious rule of Hetman Ivan Mazepa (1687-1709, figs. 1, 2). He was educated and brought up in the West and promoted European cultural influences in Ukraine.

In 1708, Mazepa, allied with Sweden, rebelled against the increasing curtailment of the political and administrative autonomy and self-governance of the Cossack polity by the autocratic Russian tsar Peter I. In retaliation, that same year, aided by local traitors, tsarist forces seized the Baturyn fortress, the stronghold of Mazepa’s uprising. In order to suppress it with ruthless terror, to avenge the unsubmissive hetman, and to punish the town for his support and the anti-Moscow revolt, the invaders executed in mass the captured Cossacks, slaughtered all of the civilians, up to 14,000 inhabitants of Baturyn, pillaged and burned it down, and took valuables to Russia.

Hetman Kyrylo Rozumovsky (1750-64) rebuilt and resettled the devastated Baturyn. He designated it again as the main city of the Cossack state, albeit not long before its abolition by the Russian empire in 1764. While Ukraine remained stateless, the former hetman capital steadily deteriorated, becoming an insignificant agricultural borough during the Soviet era.

In independent Ukraine, the government has implemented a program for the urbanization and revitalization of Baturyn. The Hetman Capital National Historical and Cultural Preserve has successfully ensured the conservation, study, and restoration of the 17-19th-century architectural monuments, the establishment and maintenance of five museums, impressive sculptural monuments and memorials glorifying the Cossack era, Mazepa, Rozumovsky, and other hetmans, and the memorialization of the victims of the 1708 Muscovite onslaught on the town, notwithstanding the current challenging conditions of wartime (figs. 1, 2).

In early modern Ukraine, the stoves faced with glazed ceramic and terracotta (unglazed) tiles or kakhli were standard for both heating and adorning residence interiors (figs. 1, 8). In Baturyn, the manufacturing of stove tiles flourished under Mazepa’s reign. They are ornamented primarily with plant and geometric relief patterns, but also with representations of Cossacks, European soldiers, angels, animals, mythical creatures, and coat of arms.

Prior to 1700, Mazepa constructed and opulently embellished his ambitious principal residence in the Baturyn suburb of Honcharivka. His palace was plundered and burned by Russian troops when they ravaged the town in 1708. The excavations of the palace’s remnants have yielded the best decorated stove tiles of about 30 variations. These artefacts are recognised as valuable specimens of Ukrainian ceramic art from the late 17th century. They were crafted by the most skilled tile-makers (kakhliari) of the Cossack state, whom Mazepa summoned from Kyiv.

Among the diverse stove tiles that archaeologists have unearthed from the debris of the Honcharivka palace, there are considerable amount of fragments of rectangular tiles featuring masterly reliefs of stylized heads of angels with outstretched wings (figs. 4-10). The more expensive tiles are glazed white, yellow, brown, and turquoise on a dark blue background, while the cheaper are terracotta with no enamel cover. The stove fronts were often revetted by glazed ceramic tiles, and plain terracotta ones were used on the sides.

On these tiles, the boyish faces of angels have the plump cheeks, massive noses, and on some fragments elongated chins. Their long yellow hair is slightly wavy, culminating on the top and bottom with ball-like curls. There are no haloes/nimbi over the angel’s heads. On the sides and bottom, their heads are enveloped by crescent-shaped stylized wings resembling a fan of white feathers. Some images of angels are more artistic, handsome, realistic, individual, and similar to their iconographic depictions. The lower corners of these tiles are ornamented with stylized lilies in relief.

Using photo collage and computer graphic techniques, researchers have hypothetically reconstructed two complete glazed ceramic polychromatic and terracotta tiles with the above-described composition (figs. 6, 7, 10). This method has also been employed for the conjectural recreation of the front elevation of the upper part of the most costly and ornate glazed ceramic multicolour tiled stove of Mazepa’s destroyed palace in Honcharivka (fig. 8). It was an important adornment of its interior, located possibly in the gala hall for official receptions, meetings, and banquets.

We believe that after completing the richest stoves in Mazepa’s manor by the Kyivan masters they, or the engaged local ceramists, produced copies of more modest terracotta tiles with the reliefs of angels and sold them to the Cossacks or burghers for facing stoves in their homes in the Baturyn fortress and its vicinities (figs. 9, 10). Following the authoritative example of the hetman palace, this motif was widespread in the tiled stoves’ revetments throughout Mazepa’s capital in the early 18th century until its fall in 1708.

The 17th-18th-century stove tiles with angels discovered by the archaeologists in Kyiv are the closest analogies to those from Honcharivka. The excavations in Kyiv have also unearthed the shards of glazed ceramic polychrome table plates and dishes with the drawings and engravings of this image from that time.

The largest number of delineations of angels’ heads with two open wings is found in the book engravings printed in Kyiv and Chernihiv in the second half of the 17th and early 18th centuries, particularly during Mazepa’s tenure. They surmount four designs of his family coat of arms on the 1691, 1696, 1697, and 1708 etchings. In the Hetmanate, decorators of stove tiles often borrowed compositions, motifs, and ornaments from Ukrainian and Western engravings, mainly from book illustrations.

Reliefs of the heads of double-winged angels are casted in the corners of the silver gilt cover of the 1701 Gospel and on the precious facing plate (shata) of the icon of the Mother of God of Dihtiarivka from the turn of the 17th and 18th centuries. Both of them were commissioned by Mazepa.

On display at the Hetman Capital National Preserve in Baturyn is the rare wooden icon of the Theotokos with the Baby Jesus (fig. 11). It likely dates to Mazepa’s era and could have belonged to him. In the icon’s corners, the high reliefs of four angel heads devoid of haloes with stylized extended wings are carved and painted in the Baroque style with folk colouring. Their child-like faces are quite realistic and each one is unique. The round rosy cheeks are somewhat enlarged more than these features of angels on the Honcharivka tiles.

The numerous dated Ukrainian engravings, the silver gilded covers of the Gospel and the icon, as well as the tiles bearing the heads of angels with outstretched wings from the facings of stoves of Mazepa’s villa and ordinary dwellings in the fortress and environs of Baturyn, testify to the popularity of this motif in both the secular and ecclesiastical arts of the Cossack state during his cadence. Perhaps, the hetman favoured it and ordered to incorporate these particular images into the designs of his heraldic emblem in several illustrations of Kyivan and Chernihivan publications, on precious repoussé works that he funded, and on the stove tiles of his headquarter.

In the mid-17th century, young Mazepa studied, served, and travelled in Poland, Germany, Holland, France, and Italy, and he was fascinated with European arts, literature, and culture. He could widely use the motif of angels/cherubs of the Renaissance tradition as a tribute to the art fashion then prevalent in the West and Kyiv, and as indication of his European cultural orientation (e.g., figs. 13-15).

In the second or third quarters of the 18th century, the façades of the Assumption Cathedral at the Kyivan Cave Monastery were embellished with massive rectangular glazed ceramic slabs featuring bas-reliefs of angels’ heads with outspread wings. After the explosion of this cathedral by the Bolsheviks in 1941, several of these details and their fragments were taken from the ruins for safekeeping to the repository of the National Preserve “Sophia of Kyiv” (fig. 12). Generally, the designs of the angels on these slabs of the Assumption Cathedral and on the much smaller stove tiles from the Honcharivka palace are comparable. However, the palette and the combination of enamel colours on the cathedral’s façade applications are quite different. They are also distinguished by the haloes behind the angel’s heads which are inherent to the depictions of saints in Orthodox iconography but are lacking on the Honcharivka stove tiles. On these slabs from the cathedral, the bas-reliefs of the stylized faces and locks of hair are more massive, pronounced, thoroughly executed, and detailed. Some images of angels are comely and distinctive. But their cheeks protrude unnaturally, more so than those on the Baturyn stove tiles with this motif (cf. figs. 4-7, 9, 10, 12).

The described above façade’s slabs of the main church of the Cave Monastery in Kyiv contain the most artistic, expressive, and colourful representations of angels in the decorative sculpture and the majolica technique of Cossack Ukraine. These 18th-century Kyivan ceramic pieces vividly reflect the influences of European Humanism and Renaissance and Baroque arts. However, they were created in the post-Mazepa period, and, therefore, could not serve as the sources of inspiration for Kyiv’s and Baturyn’s tile-masters before the sack of the hetman capital in 1708.

The examined motif of bodiless angel with only head and two extended wings was not characteristic of the Orthodox iconography of Byzantium and Kyivan Rus’. It appeared in the 15th-century sacral art of Renaissance Italy (e.g., 14, 15). From there, the angels/cherubs (putti in Italian) as a religious symbol, and later increasingly as merely ornamental element, were disseminated in both ecclesiastical and secular sculpture and painting all over Christendom during the 16th-18th centuries. At that time, this motif was also transferred to Ukraine primarily via Poland. It became favourite in the sculptural and pictorial decorations of Catholic and Orthodox churches, monasteries, castles, palaces, crypts, tombs, as well as in the secular and icon paintings, book graphics, artistic metal and earthen wares of Western and Central Ukraine.

In the 16th and early 17th centuries, invited Italian sculptors and painters introduced this motif to the arts of Galicia, Volhynia, and Kyiv, then under Polish rule. Since that time, the Kyivan tile-makers could model the reliefs and frescoes of putti in the late Renaissance style which adorned the interiors of the Assumption and St. Sophia cathedrals, as well as their delineations on Western and Ukrainian Baroque engravings, book illustrations, Catholic icons, European secular painting, toreutics, and other artistic imports.

We surmise that Kyiv’s tile-masters were also familiar with the stove tiles produced in Poland and, moreover, with those from Right-Bank Ukraine within the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. The similar features of the representations of putti on the 16th to 18th-century Ukrainian and Polish stove tiles support this view. Noteworthy are the Polish stove tiles of this time that usually bear reliefs of the stylized angels with chubby cheeks and no haloes. Their faces and wings are commonly glazed white against a cobalt background like the colouration of stove tiles with this image from the Honcharivka palace (cf. figs. 4-7, 9, 10, 13).

Analogous designs and ornamentations of puttis’ heads, hair styles, and wings are observed in the early modern sculptural embellishments of many ecclesiastical and funerary structures in Poland, Western Ukraine, and Italy. These sculptures have influenced the interpretation of this motif on ceramic stove tiles in Poland and Ukraine. In the 16th-18th century, the tile-makers could use as models or prototypes the numerous chiselled stone, stucco, and wooden painted high reliefs of putti, predominantly in a realistic manner, as displayed in the Catholic and Orthodox churches, cloisters, elite tombstones and sarcophagi. See two examples of these early modern sculptures in Rome and Florence (figs. 14, 15).

The stove tiles with angels discussed in this article are some of the best and representative pieces of the decorative-utilitarian ceramics of Baturyn during its golden age under Mazepa. The glazed multicoloured tiles have derived from the most lavish and exquisite stoves of his ruined principal residence in the Cossack capital and attest to its wealth and fine art adornments (figs. 4-8). They are rare relics of the hitherto inadequately studied palatial designs of the 17th-century Cossack rulers.

These artefacts provide a valuable insight into the culture, way of life, and artistic interests of Mazepa, the Cossacks or burghers of Baturyn, and their reception of the stimulating artistic fashions from Kyiv and the West. Thus, our research of the images on the stove tiles excavated by the archaeologists in Baturyn shed new light on the vibrant culture of the Cossack Ukraine capital and its link to European Christian civilization.

The annihilation in 1708 by Russian forces of Mazepa’s stronghold including its defenders and civilian population tragically halted life in this town for 42 years. Along with all major crafts and artistic endeavours, the local manufacturing of relief stove tiles came to an end. During the rebuilding of Baturyn by Hetman Rozumovsky in the second part of the 18th century, two-colour glazed ceramic stove tiles were imported. They feature secular scenes in then-popular Dutch style and are devoid of any Ukrainian and religious motifs.

These authors have examined the depictions of angels on the stove tiles discovered in the hetman capital in more details in a nicely published and richly illustrated booklet titled Янголи у декорі палацу Івана Мазепи в Батурині: за матеріалами розкопок (Angels in the Decoration of Ivan Mazepa’s Palace in Baturyn: A Study Based on Archaeological Findings), Toronto: “Homin Ukrainy”, 2023, 40 pp. in Ukrainian, 49 colour illustrations (fig. 3). This twelfth issue and earlier brochures in the Baturyn project series are available for purchase for $10 from the National Executive of the League of Ukrainian Canadians (LUC) in Toronto (tel.: 416-516-8223, email: luc@lucorg.com) and through CIUS Press in Edmonton (tel.: 780-492-2973, email: cius@ualberta.ca). The booklets can also be purchased online on the CIUS Press website (https://www.ciuspress.com; https://www.ciuspress.com/product-category/archaeology/?v=3e8d115eb4b3). Their publications were funded by BCU Foundation (Roman Medyk, chair) and Ucrainica Research Institute (Orest Steciw, M.A., president and executive director of LUC) in Toronto.

In 2023, the popular and authoritative Archaeology magazine of the Archaeological Institute of America, N.Y., published an important article about Baturyn as a bastion of Cossack independence and culture, its utter destruction by the Russian army, and some interesting archaeological finds at the site (https://www.archaeology.org/issues/522-2309/features/11638-ukraine-baturyn-cossack-capital).

Since 2001, CIUS and Ucrainica Research Institute have sponsored the Canada-Ukraine Baturyn Project. The Ukrainian Studies Fund in New York also supports this project with annual subsidies. In 2023-24, the research on the history and culture of the hetman capital and the preparation of associated publications were supported with donations from Ucrainica Research Institute, LUC National Executive (Borys Mykhaylets, president), LUC – Toronto Chapter (Mykola Lytvyn, president), League of Ukrainian Canadian Women National Executive (LUCW, Halyna Vynnyk, president), LUCW – Toronto Chapter (Nataliya Popovych, president), BCU Financial (Oksana Prociuk-Ciz, former CEO), Ukrainian Credit Union (Taras Pidzamecky, CEO), Prometheus Stefan Onyszczuk and Stefania Szwed Foundation (Mika Shepherd, president), and Benefaction Foundation in Toronto. The most generous individual benefactors of the Baturyn study are Olenka Negrych, Dr. George J. Iwanchyshyn (Toronto), and Dr. Maria R. Hrycelak (Park Ridge, IL).

In July, we plan to resume the excavations in Baturyn, if the wartime conditions in Chernihiv Oblast permit. In any event, both Ukrainian and Canadian scholars will continue their off-site research, publications, and public presentations on the history and culture of the hetman capital.

With the start of the full-scale Russian war against Ukraine, the Chernihiv Oblast State Administration suspended its funding of the Baturyn archaeological project. Therefore, continued benevolent support from Ukrainian organizations, foundations, companies, and private donors in North America is vital to sustain further historical, archaeological, and artistic investigations of Mazepa’s capital and the publication of the findings. Canadian citizens are kindly invited to mail their donations by cheque to: Ucrainica Research Institute, 9 Plastics Ave., Toronto, ON, Canada M8Z 4B6. Please make your cheques payable to: Ucrainica Research Institute (memo: Baturyn Project).

American residents can send their donations to: Ukrainian Studies Fund, P.O. Box 24621, Philadelphia, PA 19111, USA. Cheques should be made payable to: Ukrainian Studies Fund (memo: Baturyn Project). These Ukrainian institutions will issue official tax receipts to all donors in Canada and the United States. They will be gratefully acknowledged in related publications and public lectures.

For additional information about the Baturyn project, please contact Dr. Volodymyr Mezentsev in Toronto (tel.: 416-766-1408, email: v.mezentsev@utoronto.ca). Project participants express gratitude to Ukrainians in North America for their generous continuous support of the research on the capital of Cossack Ukraine and for helping to preserve its national cultural legacy and historical memory, which are falsified and destroyed by the Russian Federation.

___________________________________________________________________

BATURYN MASSACRE

BATURYN MASSACRE WHICH BROUGHT RUSSIAN EMPIRE TO RANK OF GLOBAL POWERS AND DESTROYED UKRAINIAN COSSACK STATE RECALLED

Euromaidan Press

Article by: Bohdan Ben

Edited by: Michael Garrood

Baturyn, a small northern Ukrainian town of 2,500 people, looks like a village with a huge museum today. Comparable to Kyiv in the 18th century and the capital of the Ukrainian Cossack state, it never regained its previous shape after the terrible massacre of 1708. In that year, Russian forces slaughtered all the 15,000 inhabitants including women and children and burnt the town to the ground.

The tragedy not only marked the decay of the Ukrainian Cossack state and its absorption into the Russian empire. The destruction of Baturyn, the greatest military arsenal and food store in Ukraine upon which Sweden’s king relied, enabled Russia to achieve victory over Sweden in the Battle of Poltava in 1709, which changed the course of the Great Northern War and secured Russia’s place among the great powers. Today, Russian President Vladimir Putin is seeking to revive this power, cynically speaking about “unity” between Ukrainians and Russians. Thanks to the efforts of historians during the last 30 years of academic freedom, the bloody nature of this “unity” has been revealed

The Baturyn massacre was never properly researched prior to Ukraine regaining independence in 1991. Since 1995, archaeologists have been digging in Baturyn: in 1995–97 and 2000–2010, archaeologists explored more than 5,000 square meters of land. Along with state funding initiated by the third Ukrainian president Victor Yushchenko, research was sponsored and conducted by the Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies (CIUS), the Pontifical Institute of Medieval Studies (PIMS) at the University of Toronto, the Ucrainica Research Institute, and the Shevchenko Scientific Society of America (NTSh-A). Importantly, the archaeological findings have fully supported data from historical documents that recorded the cruel massacre of civilians in Baturyn.

In 1667, the Ukrainian Cossack state was separated from the Zaporozhian Host, and according to the truce of Andrusovo was divided between the Moscow Tsardom and the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth along the Dnipro river. All three parts had wide autonomy, with elected Cossack hetmans and councils, although both the Commonwealth and the Tsardom tried to suppress Cossack rights.

Ivan Mazepa served as Hetman of left-bank Ukraine from 1687-1709 and was a rich patron of Ukrainian culture and “developer” of the Cossack capital Baturyn. He funded more than 40 churches out of his own money, with 200 in total built during his rule.

He also built a new residency in Baturyn and a monastery close to the city. Mazepa was always a legendary figure in European culture. Poets and composers wrote poems, operas, and dramas that

combined both historical facts and legends about Mazepa with different interpretations. One of the first and best known was the Lord Byron poem Mazeppa from 1818, with the next poem by Victor Hugo, drama by Juliusz Slowacki, operas by Marie Grandval and Pyotr Tchaikovsky, Transcendental Etude №4 and symphonic poem Mazeppa by Franz Liszt.

Mazepa’s policy was a difficult balancing act between formal loyalty to Moscow and friendly relations with the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, with an aim towards the development of economic, military, and cultural strength of the Cossack state and unification of all its parts.

However, things had worsened with the outbreak of the Great Northern War between Muscovy and the Swedish Kingdom (1700-1721). Trying to turn the Moscow tsardom into a modern empire and mobilize forces, Peter I started taking Cossack troops from Ukraine for his war, exploiting the economy of the country and concentrating power. His decree of 1707 de-facto liquidated Cossack autonomy, which Mazepa was unwilling to accept.

At this point, Mazepa allied himself with Swedish King Charles XII. This was the beginning of the tragedy of Baturyn.

In 1707 King Charles XII marched eastward towards Moscow with the best European army to push the Muscovite state away from the Baltic Sea and Central Europe. In response, the Russian Tsar Peter I resolved to use the ancient tactic of withdrawing deep into the country and destroying all supplies and storage facilities on the enemy’s way, known as scorched earth tactics. After the Swedish supply column was destroyed near Lesnaya on 9 October, the Swedish king had no choice but to search for winter rest and supplies for his main forces in Ukraine to continue the war.

For that supply purpose, Baturyn was of key importance – the Cossack capital was heavily armed with nearly 100 cannons and a 6,000-strong garrison. Mazepa had amassed a huge storage of food and gunpowder that would be enough for the entire Swedish army.

At the end of October 1708, the hetman sent a letter to Colonel Skoropadskyi of Starodub outlining the reasons that led him to conclude the Ukrainian-Swedish alliance with Charles XII: “Moscow has long had all sorts of intentions towards us, and recently began to seize Ukrainian cities, expel from them the plundered and impoverished inhabitants, and populate them with their troops. I had a secret warning from my friends, and I can clearly see that the enemy wants to take us – the hetman, all the officers, colonels and all the military leadership – into the hands of his tyrannical captivity, eradicate the Zaporozhian name and turn everyone into dragoons and soldiers, and to subject the entire Ukrainian people to eternal slavery. I learned about this and realized that Moscow came to us not to protect us from the Swedes, but to destroy us with fire, robbery and murder. And so, with the consent of all the officers, we decided to surrender to the protection of the Swedish king in the hope that he would defend us from the Moscow tyrannical yoke and restore our rights to our freedom.”

The key role of the capture of Baturyn for Russian victory is illustrated by the fact that during the subsequent Battle of Poltava, which determined the outcome of the war, the Russian army had

nearly a hundred cannons, and the Swedish army, having thirty-four cannons, used only four during the battle because of a lack of gunpowder. And this bearing in mind that the Baturyn garrison had had prior to its destruction 100 cannons and a huge storage of gunpowder.

In late October of 1708, Peter dispatched to Baturyn an entire corps of 20,000 soldiers commanded by his right-hand man Generalissimus Aleksandr Menshikov. The order was to destroy the Cossack capital and supplies there at any cost. While the Swedish army, accompanied by Mazepa, was already rushing to the city, the Russians had only five days for the siege, from 27 October to the morning of 2 September.

Initially, Menshikov tried to persuade the defenders of Baturyn to open the city, but they kept their loyalty to Mazepa. According to the Moscow chronicler Ivan Zheliabuzkyi, who described the Baturyn garrison, “He [Menshikov] sent negotiators many times demanding that the city be opened. But they didn’t listen, and began to fire from artillery.”

The garrison was commanded by four Cossack colonels with the best known Cossack infantry colonel Dmytro Chechel and also artillery captain Friedriech Königseck. Born in Prussia, Königseck served with the Cossacks for many years and had an estate near Baturyn.

Menshikov failed to capture the city during several attacks, but finally succeeded the night before Mazepa’s arrival, on 2 September. It is still unclear how he could capture this heavily armed city with a big garrison of about 6,000 men.

The three main versions are: treachery of those in one of the towers, who started firing over the heads of the Muscovites, thus allowing them into the city; treachery of the Cossack officer Ivan Nis, who showed Menshikov a secret underground passage into the city; and a false attack by Menshikov troops from the one side at night with a subsequent real attack from the other side when part of the garrison was drawn away. As contemporary Ukrainian archaeologist Volodymyr Kovalenko writes, all versions have their proofs in written sources. Excavations have also confirmed the developed underground networks under Baturyn. Therefore, all versions are possible and even all three tactics could have been used by Menshikov simultaneously.

The 19th-century Ukrainian historian Mykola Kostomarov (1817-1885) wrote about these events after thorough study of both folklore legends and written sources: “One of the Cossack officers, Ivan Nis, came to Menshikov and showed him a secret way to get into Baturyn. Nis allegedly pointed the way in the Baturyn wall. Menshikov sent soldiers there. Simultaneously, an attack was launched from the other side.”

While exact details of how Muscovites captured the city remain unclear, the fact which all sources mention is the total massacre of almost all of the 12,000-15,000 inhabitants (garrison and civilians including women, children, and infants) and the destruction of the city by fire. Only about 1,000 managed to escape.

The event was widely covered in the European press of the time, including newsletters such as the English Daily Courant, London Gazzete, French Paris Gazette, Lettres Historique, Gazette de France, and the German Wöchentliche Relation, amongst others. They contained lengthy articles

about Mazepa, his alliance with the Sweden king, and the destruction of Baturyn. Gazette de France wrote: “All the inhabitants of Baturyn, regardless of age and sex, are slaughtered, accordingly to the inhuman customs of the Muscovites. The whole of Ukraine is bathed in blood.”

According to the Lyzohub Chronicle of that time, many people were burned to death in houses. According to the Swedish historian Anders Fryxell, who wrote the history of Charles XII, “Menshikov ordered the corpses of the leading Cossacks to be tied to boards and sent floating along the Seim River so that they would give the news to others about the perdition of Baturyn.”

Cossack elites also had their homesteads outside of Baturyn, up to 15 km around the fortress, including Mazepa’s palace in Honcharivka, the first building in western European baroque style on the left bank of the Dnipro. All these, including the St. Nicholas Krupytskyi Monastery, were completely destroyed by Menshikov during the siege of Baturyn, archaeologist Volodymyr Kovalenko writes.

The city itself was burnt entirely and quickly. Only the hetman’s archive, church bells, and some of the cannons were taken away by Muscovites, while all the rest was destroyed with many people burnt to death in their houses or churches where they tried to hide.

“Archaeologists studying the remains of the foundations of the hetman’s palace in the castle discovered that the fire was so intense that fragments of glass dishes had melted, and in some places the fire had even melted bricks. The massacre and destruction were so absolute that even two decades later eyewitnesses declared that ‘the city of Baturyn is entirely deserted, and everything in its bulwarks and walls has collapsed and become overgrown, and there is no new or old structure in both the castles, only two empty stone churches,’” Kovalenko mentions.

Kovalenko is the author of many works on Ukrainian medieval history and the head of several archaeological expeditions, including Baturyn. In his lengthy article for Harvard Ukrainian Studies, Kovalenko summarizes the archaeological findings of the 1995-2008 expeditions that confirm the brutal massacre of Baturyn.

Archaeological evidence of the tragedy

During 1995-2008, archaeologists discovered hundreds of skeletons, almost a hundred buried without any traces of Christian rites. There were men, women, children, and infants with traces of violence. Kovalenko describes several examples: “Almost at the wall of the destroyed palace archaeologists discovered the burial site of a woman between the ages of twenty and thirty, whose frontal lobe shows traces of a blow inflicted by a curved weapon, such as a broadsword or a saber, which had sliced the skull neatly in half. The blow was inflicted by a tall individual who was facing the woman. The cut mark shows that the broadsword penetrated three to four cm into the skull, after which it split in two by itself. The skeleton of another young woman was found with her face shattered by a blunt instrument (possibly the butt of a musket). The bones of the lower third of the forearm of a teenage girl (15–18 years old) were shattered. Buried next to a child between the ages of nine and twelve, with a bullet hole at the back of the head, was a little girl between the ages of five and seven, whose forehead was wrapped with a thin silver band

sewn onto a red ribbon. Also found were the remains of a woman, a young man, and a teenager, all with fatal skull fractures. Archaeologists also uncovered dozens of skeletons of children between one and five years old, who had been laid in a row in shallow pits.”

The highest death toll has been ascertained by archaeologists in the castle and in the ruins of the Church of the Life-Giving Trinity, where Cossack wives and children were hiding. The results of the 2006–2009 archaeological excavations confirm what was described in the Mahilioŭ Chronicle, Kovalenko asserts, citing the Chronicle: “In keeping with the tsar’s decree, all military and city inhabitants were cut down and stabbed. In concealed spots and hiding places, wherever the sick, the gray-haired, and innocent young maidens were found, those were raped, and after being raped they were stabbed, and the monastery was plundered and [the monks] were massacred. The more important city people, saving their lives, with their treasures, with their wives, with their children, fled to the Baturyn church, built with the funds of Hetman Mazepa, and they locked themselves in there. But like lions and predatory wolves, enraged, the Muscovite army, expecting to find treasures there, [and] after dragging a cannon, they shot out the doors that were solid, and whatever lay people and clerics they found there they completely cut them down, they raped maidens on the church altars, and seized the hidden treasures there, and devastated the city and burned it down. To this day none of the people in the town of Baturyn are allowed to build homes and live.”

Many corpses of civilians were also found throughout the town that had died violently under different circumstances. The children found were mostly no older than ten years old, and there were several infants. For example: “Next to house no. 2, they uncovered the remains of a child who was buried without the benefit of a coffin—another victim of the massacre of 1708. In dig site 1 (1997), archaeologists discovered the remains (a skull) of a teenager in the cavity of a burned house located in the unfortified settlement; the burial pit cuts across the layer of the 1708 fire. Another skeleton, which was discovered in a house destroyed by the conflagration, was discovered in the trench in the fall of 2003. In 2005 archaeologists also discovered the burial site of an early eighteenth-century teenage girl, who must have hidden inside a grain pit during the slaughter in Baturyn, where she died of smoke inhalation.”

Striking is the absence of skeletons of adult males among the burial sites of the victims. Possibly, the bodies of the defenders of Baturyn as well as the bodies of Menshikov’s soldiers were buried in mass graves as yet undiscovered.

An interesting account of the aftermath of the storming of Baturyn was recorded in the diary of Peter I that Kovalenko cites: “The city of Baturyn (where Mazepa, the traitor, had his residence) was taken without great losses, and we captured the foremost thieves, Colonel Chechel and the general Cossack captain, Königseck, with several of their confederates; and we killed the rest, and burned down that city with everything and destroyed it to its foundations.”

There are many other accounts and archaeological data mentioned by Kovalenko, where one can find additional details.

Commemoration

In 2005-2010, on the initiative of the third Ukrainian president Viktor Yushchenko, the Hetman’s Capital National Historical and Cultural Reserve was established in Baturyn. Thanks to the efforts of Yushchenko and rich financial support from the Ukrainian diaspora, the Baturyn Massacre has been properly researched by historians and commemorated in Ukraine, along with another nationwide tragedy, the Holodomor, also researched and properly commemorated during Yushchenko’s presidency.

The main architectural landmark of Baturyn was the seven-domed Church of the Life-Giving Trinity, funded by Hetman Ivan Mazepa. It was one of the largest churches in the Cossack State, with a length of 38.7 m and a width of 24.1 m and was discovered during the 2007-2008 excavations. The excavations became possible thanks to joint efforts of scientists, government and patrons. Two private buildings, where the foundations of the church were located, were bought and demolished at the expense of sponsorship. The excavation area reached 1,500 square meters, which had to be studied with shovels and brushes.

In 2008, the citadel of the Baturyn fortress with the church of St. Resurrection and the original hetman’s residence of the XVII century were reconstructed on the basis of archaeological sources and became part of the museum and national reserve.

In 2016-2017, archaeologists continued excavations on the Baturyn suburb of Honcharivka, where Hetman Mazepa built his main residence – a beautiful brick palace on three floors with an attic. In 1708, the Moscow army plundered and burned this architectural landmark. In 2016-2017, the expedition also continued excavating the estate of Cossack Judge General Vasyl Kochubey (circa 1700) on the western outskirts of Baturyn.

Нижче є лінки до статтей до річниці Батуринської трагедії.

Олексій Сокирко, гарна стаття про Батуринську трагедію (1 листопада 1708)

https://localhistory.org.ua/texts/statti/popil-baturina-chomu-moskoviti-virishili-spaliti-getmansku-stolitsiu/?fbclid=IwAR07LSoV5u5vtY30CPcbVcehAY8qNBhugnpQv0GZi9Lfzz_81qxi3Tl-Qqc

Стаття журналісти: Батурин-Буча.

https://novynarnia.com/2022/11/13/vchora-baturyn-sogodni-bucha-zagybel-getmanskoyi-stolyczi-yak-nevyvchenyj-urok-istoriyi/?fbclid=IwAR2xzspSAj4NGTcU_FxTfPZFE-HcWez9V_siF5kzStLF9_DKijMSvH7Ngvg

https://cheline.com.ua/news/culture/richnitsya-baturinskoyi-tragediyi-314-rokiv-328939?fbclid=IwAR34Gx_60ucl6Rc_0KNuuGM6F_JMjaSAMvB58b4ZXkLCCklDkTjheljgkEI

Стаття англійською мовою про різанину у Батурині 1708 р.

https://euromaidanpress.com/2021/11/20/baturyn-massacre-which-brought-russian-empire-to-rank-of-global-powers-and-destroyed-ukrainian-cossack-state-recalled/?fbclid=IwAR3lRjZL1_tiknXXXUkdjls-QseMrw7cGfLIPOHG8ygsVf7J26JuiAUIq0s

Лінк до зворушливого фільму про дослідника археології Батурина й Глухова св. п. Юрія Коваленка на ютюбі: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tX-6jc4jxPI

Published in Ukrainian Echo, Vol. 37, No. 11, Toronto, June 20, 2023, pp. 1-3.

IMAGES OF HETMAN MAZEPA’S WARRIORS DISCOVERED IN BATURYN

Zenon Kohut (Edmonton), Volodymyr Mezentsev (Toronto), Yurii Sytyi (Chernihiv)

In 1995-2021, Ukrainian and Canadian archaeologists and historians conducted annual excavations in the town of Baturyn, Chernihiv Oblast (fig. 1). Last year, the field research was suspended due to Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine. Nevertheless, scholars at the Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies (CIUS) at the University of Alberta, the Chernihiv College National University, and the Hetman Capital National Historical and Cultural Preserve, despite wartime conditions, have continued their investigations and publications on the history and culture of early modern Baturyn on the basis of abundant archaeological source materials collected in previous years.

The Canada-Ukraine Baturyn Archaeological Project is administered by The Peter Jacyk Centre for Ukrainian Historical Research at the CIUS Toronto Office (https://www.ualberta.ca/canadian-institute-of-ukrainian-studies/centres-and-programs/jacyk-centre/baturyn-project.html). Prof. Zenon Kohut, a former director of CIUS and an eminent historian of the Cossack state, founded this project in 2001 and currently acts as its academic adviser. Archaeologist Dr. Volodymyr Mezentsev, research associate of CIUS in Toronto, is the project’s executive director. Archaeologist Yurii Sytyi of the Hetman Capital National Preserve heads the Baturyn archaeological team, which is based at Chernihiv University.

Fortunately, Baturyn has escaped Russian occupation, bombardments, and ruination. Its five advanced museums with their collections of antiquities of the local National Preserve, as well as the reconstructed citadel, hetman palaces, court hall, and churches of the 17th to 19th centuries, have been safely preserved and are open for the public (fig. 1).

In 1669, Baturyn was assigned as the capital of the Cossack realm, or Hetmanate. The town prospered the most during the reign of the enlightened and Western-oriented Hetman Ivan Mazepa (1687-1709, fig. 2). He and his capital became known across Europe.

In 1708, responding to Moscow’s increasingly despotic overlordship in central Ukraine, the hetman concluded an alliance with Sweden and led a revolt against the Russian tsar. That year, while putting down Mazepa’s uprising, the Muscovite army seized, sacked, and burned Baturyn to the ground. As a further punitive measure, in order to terrorize supporters of the rebellious hetman and all of Left-Bank Ukraine, tsarist troops brutally executed the captured Cossacks and state officials and massacred the entire civilian population, up to 14,000 Ukrainians in total.

After decades lying in ruins, the devastated Baturyn was rebuilt and repopulated by Hetman Kyrylo Rozumovsky (1750-64), who reinstated it as the capital of the Cossack polity. However, after its abolition by the Russian Empire in 1764 and particularly following the death of the last hetman in 1803, the town fell into decay and turned into a rural settlement while Ukraine remained stateless. In independent Ukraine, Baturyn has revived as a town and become the main centre for the preservation, study, and popularization of the historical and cultural legacy of the Cossack state capital and its rulers (fig. 1). Even during the present Russo-Ukrainian War, in the past year, nearly 11,500 Ukrainians visited the town’s museums of antiquities, famous hetman palaces, and spectacular sculptural monuments.

In early modern Ukraine, heating stoves were commonly faced with ornamented ceramic tiles, or kakhli (figs. 4-7). Tiled stoves hruby were an important adornment of the interiors in residential houses. Mazepa promoted the local manufacture of stove tiles in Baturyn, which was booming prior to its destruction in 1708. The 25-year excavations there have yielded one of the largest collections of early modern ceramic tiles in Ukraine, which is stored in the town’s Archaeological Museum. These artefacts are mainly ornamented by floral and geometric relief patterns, but there are also representations of men, angels, animals, birds, coat of arms, and religious symbols.

Tiles with images of the European officers discovered in Baturyn are unique among the earthenware of the Cossack state (figs. 4, 5). They were employed to decorate stoves at the Cossack elite homes of Mazepa’s era, remnants of which have been excavated by archaeologists. Two of these tiles, glazed green, yellow, and brown, feature similar stylized reliefs of a standing warrior in profile with a beard, moustache, and long hair or wig (fig. 4). He is dressed in a military jacket girded with a belt and wears a brim hat, holding an unsheathed sword in the upright position in his left hand. A sabre in scabbard is slung on his left hip, and a curved bow rests on the right shoulder.

Another tile from around 1700, covered by a rare turquoise-colour glazing, bears the relief full-frontal figure of a standing warrior in Baroque Western costume and footwear from the end of 17th or early 18th centuries (fig. 5). The man is dressed in a fitted mid-length military coat, extending to below his knees, with a broad hem, knee-high stockings, and heeled shoes with long tongues. His sheathed sword is slung on the right hip. Using computer graphic techniques, the colour reconstruction of the whole tile has been prepared. The broken parts of the man’s figure, including his head, wig, and tricorne hat from the turn of the 17th-18th century, as well as the left shoulder and hand, were hypothetically recreated there.

In spite of some stylization, the relief of a warrior on this tile is more realistic, detailed, and informative than other anthropomorphic depictions on such wares of the Cossack capital. The above-described three tiles likely picture European mercenary officers from Mazepa’s infantry or artillery regiments. Documents attest to the participation of several officers, primarily Germans, and rank-and-file soldiers from Central European and Balkan countries in the hetman forces. For example, the Saxon officer Friedrich von Königsek was a senior commander (heneral’nyi osavul) of the Cossack state artillery. He gave his life as a hero defending Baturyn from the Russian onslaught in 1708. At that time, foreign mercenaries served in the armies of many European countries.

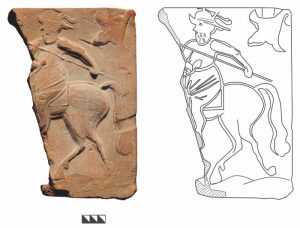

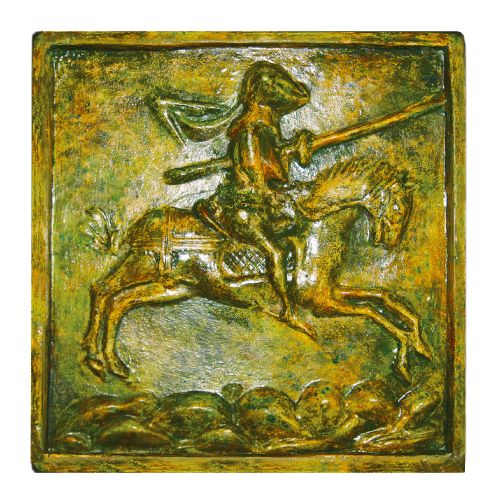

During the excavations of debris of the hetman’s residence in the citadel, as well as the dwellings of well-to-do Cossack officers (starshyna) in the former Baturyn fortress, suburbs, and environs, several fragments of terracotta (unglazed) tiles with a profile view of a Western horseman in relief have been found (fig. 6). His chest and arms are protected by the armours. Below the belt we see the flaps of the relatively short camisole. The rider’s brimmed hat is decorated with a plume. He has a beard and short hair put out below his hat on the back.

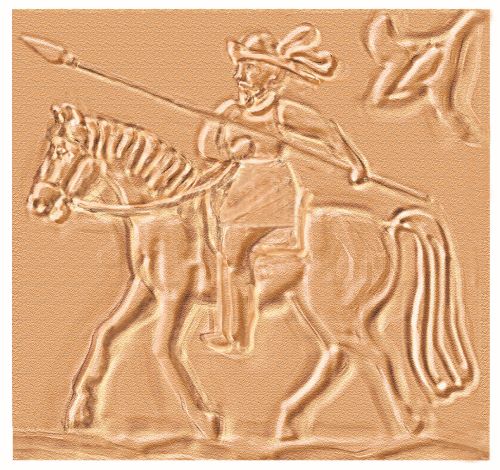

Left hand holds the spear atilt, ready for attack. On the larger tile fragment, the stretched left leg of the horsemen, wearing close-fitting pants, as well as the rear half of the walking horse, have preserved. This article presents a hypothetical computer graphic reconstruction of the entire square terracotta tile.

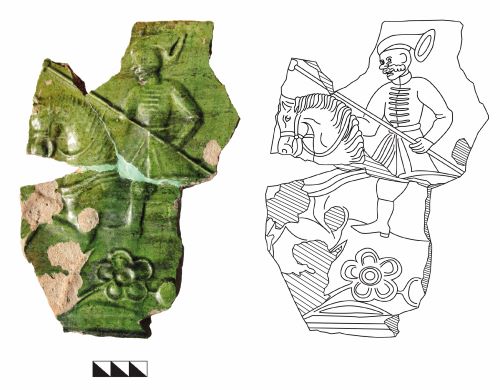

Among the Baturyn stove tiles featuring horse riders, on this fragment, human and equine anatomic forms, a garment, weapon, and military accoutrement are executed more realistically, expressively, and dynamically, with comparatively less stylization and local folk features. Based on his uniform, armament, and armour, this horseman can be associated with Western European heavy cavalryman, a cuirassier or reiter, from the Thirty Years’ War (1618-48). The authors believe that Baturyn’s tile-makers (kakhliari) copied this representation from a Western realistic drawing or engraving of the 17th or early 18th century (e.g., fig. 9).The fragment with relief of a Cossack on horseback, covered by green glazing, which has been unearthed in the hetman capital, is a remarkable specimen of the Cossack genre tiles (fig. 7). The torso and head of this horseman are turned in 3/4 front pose, while his leg and the horse are shown in profile. His knee-length typical Cossack coat (zhupan or kuntush) has a wide skirt. It is girded with a belt and ornamented by galloons on the chest. He is dressed in traditional broad trouser or sharovary and low-heeled boots.

This Cossack has a long and luxuriant moustache. In his left hand he holds a spear in the high ward position. The forelegs of the cantering horse are partly preserved. Applying computer graphic extrapolation techniques, line drawing and hypothetical shaded colour reconstruction of the complete composition on a square, green-glazed ceramic tile have been prepared.

It is noteworthy that this artefact from Mazepa’s time displays one of the earliest authentic images of the sharovary in Ukraine (fig. 7). This style of trouser was a characteristic component of the male ethnographic costume throughout central and eastern Ukraine in the 18th and 19th centuries.

The relief of the mounted hetman’s Cossack in national dress and footwear was fashioned in the stylized distinctive vernacular manner. Presumably, this tile portrays a rank-and-file Cossack from the light cavalry regiment known as kompaniitsi, who were armed with spears. These cavalrymen together with the infantry musketeers or serdiuky served as the hetman’s bodyguard and most reliable professional elite troops. They were devoted to Mazepa and provided the main basis for his power.

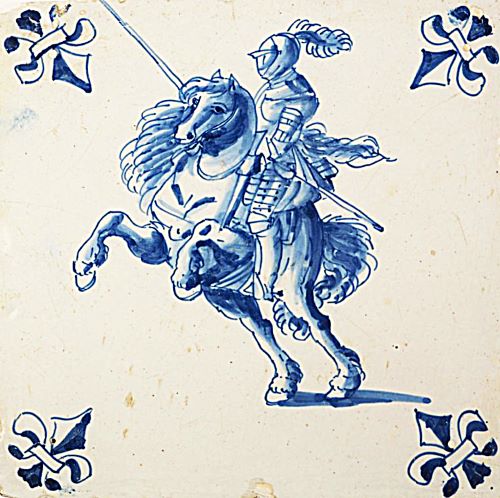

Tiles bearing similar motifs of mounted Cossacks carrying spears or sabres were widespread across 17th-18th-century central Ukraine. They symbolised Cossack’s glory and epoch and often faced the stoves in residences of hetmans, colonels, and other Cossack officers.

Except for the mounted cuirassier dating to the first part of the 17th century, the local tile makers were able to depict the contemporaneous Cossacks and European mercenaries whom they observed in Mazepa’s capital. Therefore, these artefacts are valuable visual sources for the study of visages, haircuts, clothing, footwear, ornaments, weapons, military accoutrements, horse harness, and the multinational composition of hetman’s army (figs. 4, 5, 7).Among the settlements of the Cossack realm, Baturyn is unique for the prevalence in its Mazepa-era tile finds of images of the Western officers and soldiers. This can be explained by its status as the capital of the Ukrainian Cossack state, including hetman’s residences and troops with many foreign mercenaries. Furthermore, Baturyn was engaged in broad-ranging international diplomatic, commercial, and cultural relations, as well as imported from Europe numerous illustrated publications and fine artworks, particularly during Mazepa’s reign.

Having received his university education in Poland, Germany, Holland, France, and Italy, Mazepa was fascinated with the European arts, literature, and culture. Written sources testify that during his hetmancy Western books, newspapers, and portrait paintings were brought to Baturyn. He could order local artisans to decorate stove tiles at his palace in the citadel with representations of armed European cavalrymen, and also provide them with original graphic templates, for instance, some Western book illustrations from his own unrivalled library or from court collections of engravings and paintings.

Probably, following the authoritative example of their hetman, government officials, Cossack officers, and some well-to-do burghers in Baturyn also employed similar Western military motifs in adorning the tiled stoves at their homes (figs. 4-6). Thus, the emulation of the hetman’s decorative practice and the local manufacturing of these popular stove tiles resulted in their wide dissemination throughout Mazepa’s capital until its sack in 1708.

The masterly reliefs of mounted knights fashioned in the Gothic style on Polish stove tiles in the 15th and 16th centuries were the prototypes for the designs of Cossack horsemen in relief on tiles produced in Baturyn and Ukraine during the next two centuries (cf. figs. 7, 8). We also surmise that the ceramists in Mazepa’s capital used as templates some professional drawings of infantry officers and cavalrymen on Dutch majolica revetment tiles, or their Central European imitations, as well as Western engravings with analogous military subjects from the 17th and early 18th centuries (e.g., fig. 9). However, these masters creatively reinterpreted, adapted, and stylized the realistic graphic images of European warriors and their horses to a considerable degree, transforming them into relief moulding and colour glazing techniques on stove tiles, in keeping with the tradition of Ukrainian decorative applied ceramic art of that time.

Indeed, the anthropomorphic tiles are the most informative, thought-provoking, and representative Baturyn earthenware items from its golden age during Mazepa’s illustrious rule (figs. 4-7). Their depictions allow us to trace the cultural connections between the hetman capital and the West, including the stimulating influence of Baroque drawings on the town’s decorative ceramics.

These artefacts provide an important new insight into the culture and lifeways, artistic tastes, and Western orientation of the hetman, the Cossack officer class, and wealthy burghers in Mazepa’s capital. Thus, our research on the anthropomorphic stove tiles excavated by the archaeologists in Baturyn helps to elucidate the high culture of the Cossack Ukraine capital and its dynamic development within the sphere of European civilization.

Regrettably, after the sheer destruction of Baturyn by the Russian army in 1708, even during its revitalization under Hetman Rozumovsky in the second half of the 18th century, local manufacturing of stove tiles embellished with human, animal, Christian, heraldic, and other reliefs never recovered in the town. These artistic skills perished along with the exterminated Cossack defenders, craftsmen, artists, and all inhabitants of Mazepa’s razed capital. Only thanks to the 25-year excavations of its ruins archaeologists have discovered, reconstructed, and analysed the discussed above four tile samples with the warriors from the devastated capital of the Cossack state (figs. 4-7).

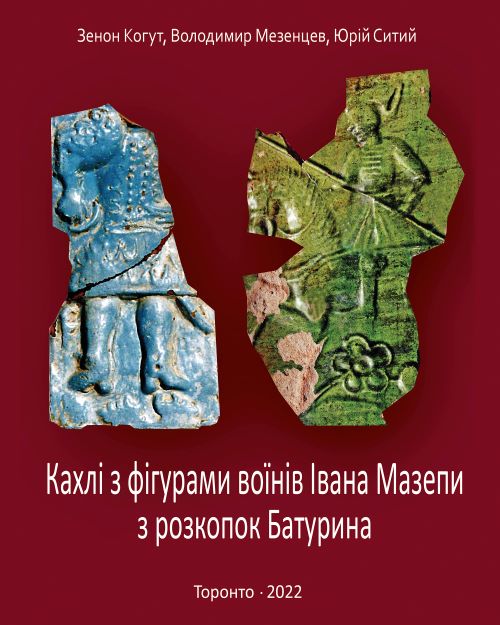

For more anthropomorphic tiles that have been unearthed there and its detailed examination, please see a nicely published richly illustrated booklet for the general public and scholars by these authors titled Кахлі з фігурами воїнів Івана Мазепи з розкопок Батурина (Stove Tiles Featuring Ivan Mazepa’s Warriors from Excavations of Baturyn), Toronto: “Homin Ukrainy”, 2022, 44 pp. in Ukrainian, 61 colour illustr. (fig. 3). This eleventh issue and earlier brochures of the Baturyn project series are available for purchase for $10 from the National Executive of the League of Ukrainian Canadians (LUC) in Toronto (tel.: 416-516-8223, email: luc@lucorg.com) and through the CIUS Press in Edmonton (tel.: 780-492-2973, email: cius@ualberta.ca). The booklets can also be purchased online on the CIUS Press website (https://www.ciuspress.com; https://www.ciuspress.com/product-category/archaeology/?v=3e8d115eb4b3). Their publication was funded by the BCU Foundation (Roman Medyk, chair) and the Ucrainica Research Institute (Orest Steciw, M.A., president and executive director of LUC) in Toronto.

Since 2001, CIUS and the Ucrainica Research Institute have sponsored the Canada-Ukraine Baturyn Project. In 2022, CIUS supported it with a grant from the Dr. Bohdan Stefan Zaputovich and Dr. Maria Hrycaiko Zaputovich Endowment Fund. The Ukrainian Studies Fund in New York also supports the Baturyn project with annual subsidies. In 2022-23, the research on the history and culture of the hetman capital and preparation of associated publications were supported with donations from the Ucrainica Research Institute, the National Executive of LUC (Borys Mykhaylets, president), LUC – Toronto Branch (Mykola Lytvyn, president), the National Executive of the League of Ukrainian Canadian Women (LUCW, Halyna Vynnyk, president), LUCW – Toronto Branch (H. Vynnyk, president), BCU Financial (Oksana Prociuk-Ciz, CEO), the Ukrainian Credit Union (Taras Pidzamecky, CEO), the Prometheus Foundation, the Benefaction Foundation in Toronto, and Zorya Inc. (Greenwich, Conn.). The most generous individual benefactors of the Baturyn study are Olenka Negrych, Dr. George J. Iwanchyshyn (Toronto), and Michael S. Humnicky (Murfreesboro, TN).

Soon after the victory of the Armed Forces of Ukraine and the liberation of southeastern Ukraine from the Russian invaders, we plan to renew annual excavations in Baturyn. In any case, both Ukrainian and Canadian scholars will continue their off-site research and publications on the history and culture of the hetman capital. Clearly, until the end of the war, it will be impossible to obtain any funding for this academic project in Ukraine. Therefore, continued benevolent support from Ukrainian organizations, foundations, companies, and private donors in North America is vital to sustain further historical, archaeological, and artistic investigations of Mazepa’s capital and the publication of its findings this year. Canadian citizens are kindly invited to support this ongoing work with donations by cheque sent to: Ucrainica Research Institute, 9 Plastics Ave., Toronto, ON, Canada M8Z 4B6. Please make your cheques payable to: Ucrainica Research Institute (memo: Baturyn Project).

American residents can send their donations to: Ukrainian Studies Fund, P.O. Box 24621, Philadelphia, PA 19111, USA. Cheques can be made out to: Ukrainian Studies Fund (memo: Baturyn Project). These Ukrainian institutions will issue official tax receipts to all donors in Canada and the United States. They will be gratefully acknowledged in related publications and public lectures.

For more information about the Baturyn project, readers can contact Dr. Volodymyr Mezentsev in Toronto (tel.: 416-766-1408, email: v.mezentsev@utoronto.ca). The authors kindly thank Ukrainians in North America for their generous support of the historical and archaeological research on the Cossack capital in past years and for helping to our historical front during the genocidal war waged by Russia against Ukraine and its Cossack heritage.

9 CAPTIONS FOR 12 PICTURES

|

|

|

ig. 1. 17th-century Baturyn citadel with the hetman’s residence, reconstructed in 2008 based on archaeological data. Aerial photo from the archives of the Hetman Capital National Preserve. Photos of the structures by V. Mezentsev.

Fig. 2. “Glorification of Ivan Mazepa, Hetman of Ukraine”. Painting by Ihor Hrechanovsky with a panorama of the Baturyn citadel, 2020. Museum of the History of the Poltava Battle in Poltava. Photo by O. Hrechanovsky.

Fig. 3. Richly illustrated booklet titled in translation “Stove Tiles Featuring Ivan Mazepa’s Warriors from Excavations of Baturyn” (Toronto: “Homin Ukrainy”, 2022).

Fig. 4. Glazed ceramic stove tile featuring a European mercenary officer of Mazepa’s era. Photo by A. Konopatsky, line drawing by S. Dmytriienko. All tiles excavated at Baturyn are in the collections of the Museum of Archaeology at the Hetman Capital National Preserve.

Fig. 5. Glazed ceramic tile bearing the relief of a European mercenary officer from the stove at Vasyl Kochubei’s mansion in Baturyn, ca. 1700. Photo by A. Konopatsky, contour rendering and hypothetic computer graphic reconstruction of the whole tile by S. Dmytriienko.

|

|

Fig. 6. Fragment of a terracotta tile of Mazepa’s time with the relief of a Western European heavy cavalryman of the early 17th century. Photo by A. Konopatsky, line drawing and hypothetic computer graphic reconstruction of the entire tile by S. Dmytriienko.

Fig. 7. Glazed ceramic tile fragment depicting a mounted Cossack from Mazepa’s troops. Photo by A. Konopatsky, contour drawing and hypothetic computer graphic reconstruction of the complete tile by S. Dmytriienko.

Fig. 8. Glazed ceramic stove tile featuring the relief of an armoured knight on horseback, 15th-16th century. National Museum in Kraków, Poland. Photo by V. Mezentsev.

|

|

Fig. 9. 17th-century Dutch ceramic revetment tiles with the drawings of a standing officer and a mounted cuirassier. Left photo is from an open Internet-site. Right photo is from the website of the Regts – Delft Tiles, Holland, reproduced courtesy of this firm (https://www.regtsdelfttiles.com/antique-delft-tile-with-a-knight-and-horse-full-gear-17th-century.html).

Mezentsev V.I. Original images and reconstructions of I. Mazepa’s princely coat of arms

This article for the first time examines all of the graphic and relief representations of the princely armorial bearings (“herb”) of the Ukrainian Cossack ruler, Hetman Ivan Mazepa (1687–1709), which were prepared between the eighteenth and twenty first centuries and are known by the present. It demonstrates with figures, describes, analyses, and compares the original published designs of his heraldic emblem on the engraving at Johann Siebmacher’s, Grosses und allgemeines Wappenbuch: Fürsten des Heiligen Römischen Reiches: M–Z. Band I. 3. III. Nürnberg, 1887 (Great and Universal Collection of Coat of Arms), on the glazed ceramic tiles (“kakhli”) facing stoves at the residence of Chancellor General Pylyp Orlyk in the town of Baturyn, and on the silver seal of 1707–1708 from the collection of the Sheremet’iev Museum in Kyiv. Special attention is devoted to exploring the hitherto little known early modern heraldic symbols of a princely power (“korony, mantii”) of the Ukrainian and Western traditions.

The fragments of these stove tiles were discovered during the 2017–2020 excavations of the remnants of P. Orlyk’s home in Baturyn, Chernihiv province, Ukraine, which was the capital city of the seventeenth-and eighteenth-century Cossack state or Hetmanate. This Canada-Ukraine archaeological project is sponsored by the Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies (CIUS) at the University of Alberta and the Ucrainica Research Institute in Toronto, Canada. The Baturyn project is administered by The Peter Jacyk Centre for Ukrainian Historical Research at CIUS Toronto Office (https://www.ualberta.ca/canadian-institute-of-ukrainian-studies/centres-and-programs/jacyk-centre/baturyn-project.html). The Ukrainian Studies Fund in New York, the Chernihiv Oblast State Administration, and the Vasyl Tarnovsky Chernihiv Regional Historical Museum support the archaeological and historical investigations of early modern Baturyn with annual grants. The most generous private benefactors of this project are the late artist Roman J. Wasylyszyn (Philadelphia, PA, USA), artist Ralph C. Roe II (Greenwich, CT, USA), Dr. George J. Iwanchyshyn, and Ms. Love Helen Negrych (Toronto).

The author has shown that these original heraldic graphical, archaeological, and sphragistic sources represent the veracious indisputable visual evidence of the legitimate princely status of I. Mazepa. They corroborate and substantially supplement the limited and divergently interpreted by some historians the eighteenth- and nineteenth-century Austrian and German written archival and published information that in 1707 Kaiser Joseph I of the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation honoured this Ukrainian hetman with the prestigious title of prince of this empire ("Sacri Romani Imperii Princeps” in Latin or “Reichsfürst” in German) for his vigorous defence of Christendom against Ottoman expansion.

This article also reviews the obsolete hand-drawn versions by the nineteenth- and twentieth-century historians and artists attempting to recreate the polychrome coat of arms of I. Mazepa as imperial prince. It focuses on the more advanced, detailed, and grounded in sources recent reconstructions of his multicoloured armorial bearings prepared with the computer graphic technique. They are based on the close research of authentic relief depictions preserved on the 1707–1708 stove tiles excavated in Baturyn and on the synchronous silver seal from the Sheremet’iev Museum in Kyiv.

These locally manufactured artefacts featuring unique compositions and decorations of I. Mazepa’s princely arms are valuable and informative examples of the Ukrainian baroque heraldic art. Their study and reconstructions provide an important new insight into the heraldry and representative culture of the Cossack elite and its European connections, which are the popular topics of current Ukrainian historical scholarship.

Key words: designs of I. Mazepa’s princely coat of arms, original graphic and relief heraldic images, hand-drawn and computer graphic reconstructions, Baturyn, the Ukrainian Cossack state or Hetmanate, the Holy Roman Empire.